Worshiped for the sense of euphoria it brings and loathed for the depression that follows as its effects wear off, opium is one of the most addictive drugs known to man.

Visitors to the Hall of Opium in Chiang Rai will learn about the drug’s medicinal benefits, its social implications, the wars it has caused and much, much more, and leave this fascinating museum with a better understanding of why the problem of illegal drugs must be resolved.

Encompassing a 250-rai area in the Golden Triangle Park, the venue is wisely constructed, carved into a mountain and accessible only through a 137-meter cave entrance that draws the visitor deeper into the dark realm of a world with the agonized faces of the addicted on the wall.

The first references to opium were found in Sumerian medicinal texts. It was used for medical and ritual purposes in ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt, spreading later to Europe and the Americas. But, as the curators suggest through the exhibits, the major change in opium use and abuse occurred only when it became a major commercial commodity introduced by Britain to China and other Southeast Asian nations in the 1700s.

Wanting silk and tea from China but no longer wanting to pay in silver, Britain sought to fix the imbalance by trading with the opium it was getting from India. From mixing it with tobacco, the Chinese went to smoke pure opium and the habit quickly spread to all walks of life. This eventually, this led to the Opium Wars between China and Britain, and later other Western powers.

To historians, the wars severely weakened the Manchu Dynasty and led to drastic changes in China.

When the addictive drug reached Siam, the Chinese migrants were the first to pick up the habit. With the legal opium trade thriving, Siam was selected as a representative of the extensive opium production and trade, with growing and planting of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) concentrated in the Golden Triangle.

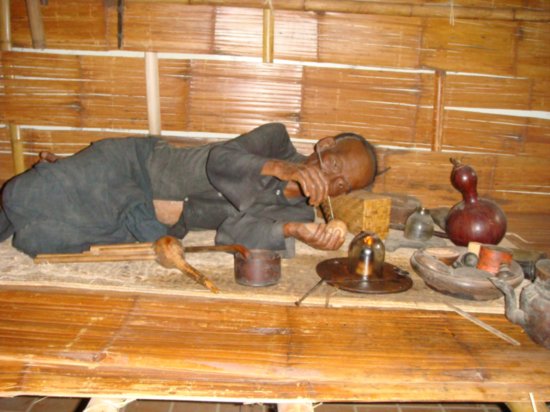

One of the most powerful images in the Hall of Opium is the display of a life-sized man, dressed in Manchurian clothes and with long, braided hair. He is lying on a wood bed and holding a long opium-smoking pipe. With one electronically controlled foot moving back and forth, he is apparently in a state of euphoria.

A little further on is the smoking den where visitors learn about the health impacts of the drug. A few steps away from the exhibits of smoking pipes and weights used to measure opium and other items associated with consumption is a display of images of those who discovered too late that it’s an uphill task to overcome addiction.

There are lengthy explanations of the international treaties to stop opium consumption and the present-day illegal drug trade while the Hall of Reflection offers a quiet place to sit and think what you have seen and what you can do to stop the proliferation of the associated dangers.

Although it takes a while to walk through the 5,600-square-metre museum, any fatigue is washed away by the interactive exhibits. Children will enjoy the gun-fighting scenes from the notorious Opium Wars while adults will probably be more interested in the model of the upper half the body. Push the buttons showing natural opium and drugs derived naturally and synthetically from the poppy and the exhibit shows you what part of the body the drugs are affecting.

The exhibit of the equipment used for making opium filled me with admiration for the opium makers. They made the opium on site, with large semi-circular pans and wooden sticks. The raw opium was boiled with firewood, until it was as sticky as caramel. Then, the black caramel was poured into tin boxes, ready for delivery.

It’s fascinating to learn how dangerous a flower as beautiful as the opium poppy can be and even more fascinating to discover that of the more than 100 other Paperver species – including the red remembrance poppy we wear to remember soldiers who have lost their lives in wars – opium can be made from only two kinds. One of them is the poppy grown in the northern border region of Thailand, which has been eradicated from the Kingdom and the another, far more rare, in the high altitude of the Alps.

It is not surprising that the Hall of Opium in 2004 won Pacific Asia Travel Association’s Education and Training Award for its sensitive and detailed exhibition and museum on the history of opium and the impact of illegal drugs. It is also dubbed as one of the best exhibitions in Asia.

On the day I was there, most of the other visitors were foreigners, chiefly Japanese and Chinese. The journey was worthwhile, as it is a reminder to all that no matter how popular, a dangerous commodity should never be promoted. –

Achara Deeboonmee POISONOUS PLANT

The Hall of Opium is sponsored by the Mae Fah Luang Foundation.

It’s located in Moo 1 Ban Sop Ruak, Tambon Wiang, Chiang Saen, Chiang Rai 57150.

Call (053) 784 444-6 or e-mail [email protected].